Jumpform v slipform

Contents |

[edit] Introduction

Jumpform and slipform are both systems of concrete construction that use a self-climbing formwork to construct multi-storey structures, typically building cores and shafts, as well as chimneys and silos. They are both climb-form systems.

In both cases, formwork into which concrete is poured, climbs vertically up the structure being constructed; sometimes this is from power provided by hydraulic rams and electric motors and can mean that craneage is reduced to a minimum. Both systems feature one or more decks or platforms surrounding the construction for workers to carry out the necessary operations as construction proceeds, such as pouring and monitoring concrete compaction, placing reinforcement and finishing the concrete.

Whether slipform or jumpform, the formwork is supported on the concrete that has already been cast below it, so it does not rely on support from other parts of the building; this allows the shaft or core to progress ahead of the rest of the building works.

However, there are important differences between the two systems in terms of operation, speed and the result achieved.

[edit] Jumpform

Typically, jumpform is used on buildings more than five storeys high, although if a fully-climbing system, it can be applied to 20-storeys and more.

Jumpform is characterised by progression in a series of steps or ‘jumps’, progressing to the next section only after the concrete in the previous one has achieved the necessary strength. For example, after a 2m section has been poured and set, the formwork is ‘jumped’ to pour the next 2m section. The system is particularly suited to situations where the resulting joints between jumps will be concealed at every level e.g by the floors of a building.

Jumpform can be very productive, fast and efficient yet minimise the labour required and craneage costs. There are three main type of jumpform:

- Normal – involves formwork that is lifted off by crane and reattached at the next level above.

- Guided – similar to the normal method above but units remain anchored to the structure during the raising operation by crane. This method can be safer and more controlled.

- Self-climbing – this type of jumpform is raised on rails and so does not require a crane.

There could also be trailing platforms and screens that can be used to help workers apply any required finishing to the concrete or retrieve anchors used on the pour below.

Jumpform systems are highly engineered and so can be quickly and accurately adjusted in all planes. However, they depend on the availability of a skilled workforce on site.

[edit] Slipform

Slipform is a continuous pour system involving a self-climbing formwork that supports itself on the core or shaft being constructed, moving slowly over the concrete as it is cast in a continuous, monolithic pour. It can be used to achieve tapered structures with walls of diminishing thickness and is regarded as being more economical when used for structures over seven storeys high.

Slipform typically has three platforms – a lower platform for concrete finishing; a middle platform at the top level of the concrete being poured, and an upper platform for storing materials.

Normally advancing at a rate of around 300mm per hour, slipform can be regarded as a method of vertical extrusion. This can result in a smooth, continuous concrete finish without any joints, an effect which may be required where the finished structure will be visible e.g bridge pylons or a chimneys. However, slipform may entail higher costs due to the required round-the-clock working until the necessary height of structure has been achieved. Like jumpform, it also requires the availability on site of a small, highly-skilled workforce.

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

Featured articles and news

UKCW London to tackle sector’s most pressing issues

AI and skills development, ecology and the environment, policy and planning and more.

Managing building safety risks

Across an existing residential portfolio; a client's perspective.

ECA support for Gate Safe’s Safe School Gates Campaign.

Core construction skills explained

Preparing for a career in construction.

Retrofitting for resilience with the Leicester Resilience Hub

Community-serving facilities, enhanced as support and essential services for climate-related disruptions.

Some of the articles relating to water, here to browse. Any missing?

Recognisable Gothic characters, designed to dramatically spout water away from buildings.

A case study and a warning to would-be developers

Creating four dwellings... after half a century of doing this job, why, oh why, is it so difficult?

Reform of the fire engineering profession

Fire Engineers Advisory Panel: Authoritative Statement, reactions and next steps.

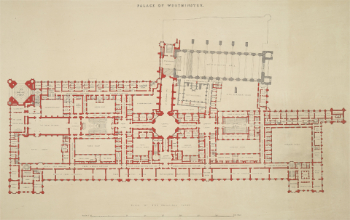

Restoration and renewal of the Palace of Westminster

A complex project of cultural significance from full decant to EMI, opportunities and a potential a way forward.

Apprenticeships and the responsibility we share

Perspectives from the CIOB President as National Apprentice Week comes to a close.

The first line of defence against rain, wind and snow.

Building Safety recap January, 2026

What we missed at the end of last year, and at the start of this...

National Apprenticeship Week 2026, 9-15 Feb

Shining a light on the positive impacts for businesses, their apprentices and the wider economy alike.

Applications and benefits of acoustic flooring

From commercial to retail.

From solid to sprung and ribbed to raised.

Strengthening industry collaboration in Hong Kong

Hong Kong Institute of Construction and The Chartered Institute of Building sign Memorandum of Understanding.

A detailed description from the experts at Cornish Lime.